America’s old-growth forests are threatened by logging and climate change. Can a government-mandated inventory preserve what’s left?

On Earth Day 2022, President Biden penned an executive order mandating that the government do something unprecedented: catalog every old-growth tree in the nation. The Forest Service’s oldest employee, Smokey Bear, had his work cut out for him. This effort could have the power to permanently preserve one of the most valuable carbon sinks in the world, the so-called “Amazon of North America” — the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

There are many strategies for protecting these special trees, and over the years activists and scientists alike have tried them all, from responsible planting of symbiotic species to aluminum foil blankets for fire protection and, in one extraordinary case, a woman who lived in a giant redwood tree for two years, putting her own body between the axes and the lichen-covered trunk. These tactics have saved some trees, but they haven’t been able to achieve legal protection enshrined in federal law. Until now.

Let’s conceptualize a forest as being like a four-floor building. You have your overstory, canopy, understory, and shrub levels. Now let’s board the elevator in that building and take it from the ground floor to the basement floor. When the doors slide open, you would be face to face with a collage of wildlife, rivaling the variety of the upper floors. Wild silky mycelium threads in pastel and light white shades weave around tree roots, hibernating banana slugs, pocket gophers lounging in their burrows, their neighbors, the voles, hiding from owls next door.

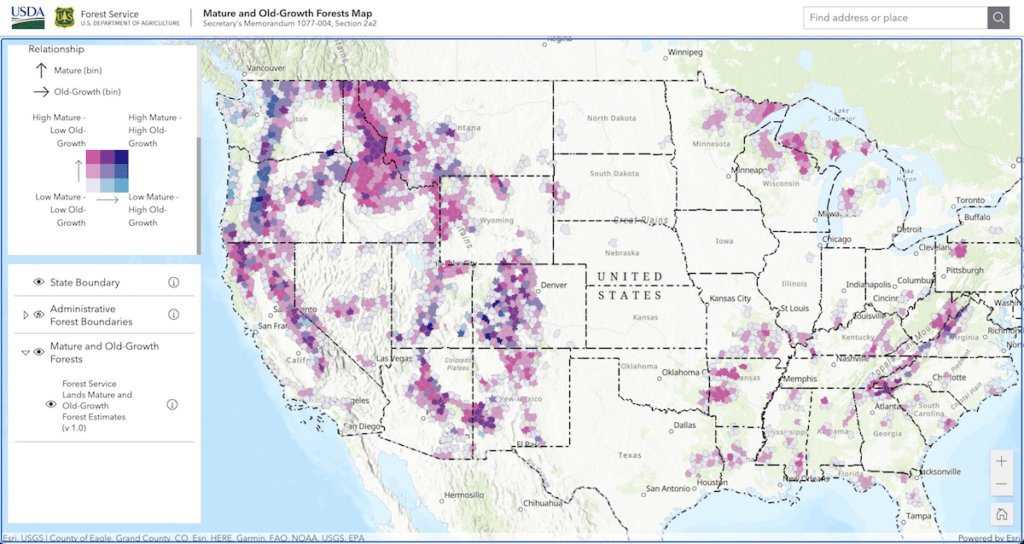

One year after Biden’s executive order, on April 20, 2023, the U.S. Forest Service released the first ever inventory detailing all known stands of old-growth forest in the nation. Old-growth refers to trees that have never had their life cycle ended by a saw, fire, disease, erosion, or pests. What was previously shrouded in misty mystery is now revealed. A series of charts and maps lays out what advocates have been fearing for decades: there’s not much old-growth forest left. The report sets forth an ambitious plan to guard these forests’ climate-stabilizing trees against further threats.

The other two goals of the executive order were to set targets for reforestation and analyze opportunities to put such efforts in place on state, Tribal, and private lands. The Forest Service responded to this mandate by launching a new interactive online tool called the Forest Service Climate Risk Viewer, which displays the climate threats and vulnerabilities of each region of the nation. This tool will serve as a treasure map; X marks the spot for conservation.

Policy and Interests: Old-growth protection policy in the United States is not completely unprecedented. In the 1990s, conflict between environmental activists and timber workers in the Pacific Northwest prompted President Clinton to organize a convergence of minds in Oregon and pass the Northwest Forest Plan in 1994. Along with categorizing the northern spotted owl as an endangered species, a keystone in its old-growth habitat, this plan also set aside 30%, or 7.4 million acres, of federal land as Late Successional Reserve in an effort to transition that land into old-growth. Succession is the process by which a forest recovers from a disruption in stages. Unfortunately, due to the influence of timber interests, this plan was never realized to its full extent and was only moderately effective.

A snapshot of old-growth forests

The table you sit at, the notebook you write in, the house where you live — all were likely carved, pulp processed, or whittled from tree timber. Wood is such a ubiquitous material, we hardly notice it, nor realize that it is a finite resource — so finite that many companies and federal agencies have been tapping our most ancient and important cache — mature and old-growth forest (MOG).

If you have ever driven down a country road and passed a corn field, you have also witnessed what most monoculture timber farms look like — neat rows of evenly spaced trees as far as the eye can see. In 2019, U.S. lumber production amounted to about 45,423 million board feet. Those planks are largely harvested from both tree farms and wild growth on public lands — land owned by National Parks and Forests. So while the government does make efforts to protect those lands, it also farms them.

According to the Forest Service’s maps, the spread of old-growth across the country varies significantly. The West Coast has a much higher concentration compared with the East. And the age of maturity of old-growth trees can be drastically different depending on the species. “For instance,” the report explains, “old-growth sequoias in California can be thousands of years old and upwards of 250 feet tall with a 30-foot or greater trunk diameter, while an old-growth stand of dwarf pitch pine in New Jersey may include trees that are hundreds of years old, roughly 14 feet tall and only several inches in diameter.” States like New Jersey and Massachusetts were found to contain only parcels of younger trees, although this does not mean that there are not older individual trees scattered around.

Climate Implications

The 16-foot-diameter tree cross section on display at the Museum of Natural History was 1,400 years old at the time it was felled. It’s a giant sequoia, one of the most grandiose species. This is what the general public envisions as an old-growth tree. In contrast, the juniper-pinyon, a scrubby and less charismatic tree, is the most numerous old-growth tree species in the country, and equally important.

A study published in the journal Nature found that the age of a tree is directly correlated with its carbon capacity; in other words, “large, old trees do not act simply as senescent carbon reservoirs but actively fix large amounts of carbon compared to smaller trees.” According to the Arbor Day Foundation, a mature tree removes almost 70 times more pollution than a newly planted tree.

Let’s conceptualize a forest as being like a four-floor building. Now let’s board the elevator in that building and take it from the ground floor to the basement floor. When the doors slide open, you would be face to face with a collage of wildlife, rivaling the variety of the upper floors. Wild silky mycelium threads in pastel and light white shades weave around tree roots near hibernating banana slugs, pocket gophers lounging in their burrows, and their vole neighbors hiding from owls next door. All these organisms interact to stay alive. They rely on the tree’s daily delivery of nutrients to the soil. When a tree has been growing for a very long time, these inter-species relationships are tightly linked, like old friends. The death of such a tree would be devastating to its community.

The climate impacts of cutting down old trees would also be devastating. A study published in 2022 calculated that if most MOG trees on federally owned land are logged over the next decade, the loss of those trees would bump up the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere by the equivalent of a roughly 10 percent increase in the United States’ current total annual emissions.

Grassroots groups are key

In the past, the Forest Service has collaborated with native tribes on various projects. This new report, along with the recently released Department of the Interior strategic plan, solidifies that partnership as an ongoing fixture in future endeavors. It only makes sense that the government should seek the wisdom of the peoples whose ancestors have occupied these lands for many millennia. Native consultant Eddie Sherman, of the Diné and Umóⁿ'hoⁿ tribes, is leading the way. He recently partnered with the NRDC on a forest management project and is working hard to ensure the ongoing involvement of local native people.

It only makes sense that the government should seek the wisdom of the peoples whose ancestors have occupied these lands for many millennia. Native consultant Eddie Sherman, of the Diné and Umóⁿ'hoⁿ tribes, is leading the way.

This new approach doesn’t necessarily mean that no old-growth forests will ever be cut again. A Politico article recently highlighted the contradictory actions of North Carolina state foresters, who, despite their declared conservation goals, still plan to move ahead with their recently updated goal of boosting timber harvesting numbers, or put another way, chopping down trees older than our grandparents.

“Federal agencies continue to target large, valuable trees, valuing timber production over the climate, water, and biodiversity values these trees provide,” said Victoria Wingell, leader of the organization Oregon Wild, in an email. “This [Forest Service report] is a huge step towards permanent protections, but our work isn't done yet. There are a number of threatened forests in Oregon that could be lost if strong protections aren’t enacted soon.” A recent report put out by Climate Forests counts 23 pending timber sales.

Another Oregon-based organization, Cascadia Wildlands, has been toe-to-toe with the Forest Service about these timber sales for years. One of the organization's main tactics for fighting unnecessary logging is visiting and assessing the proposed sites. These “field checks,” though simple in theory, are quite powerful in practice. The group leads a hike — of their members and regular members of the general public — into the woods and, using the Forest Service’s maps, they review the site based on several criteria. They take note of tree age, spacing, biodiversity, evidence of wildfire scars, presence of fungi and critters, balance of canopies, existence of waterways, and more. Depending on their conclusions regarding these criteria and the relative ecological importance of the area, they may write to the Forest Service and encourage them to limit or cancel their logging. These hikes have been successful in helping to stop multiple timber sales in the past, including the Flat Country timber sale, halted earlier this year.

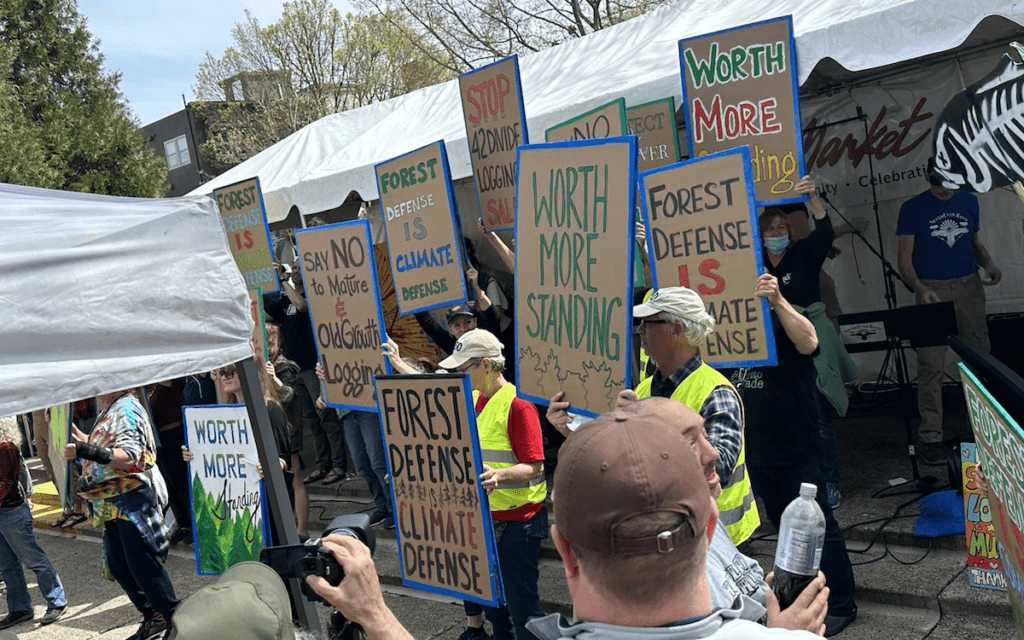

On Earth Day, Oregon Wild and several other organizations made old-growth forest protection the centerpiece of their calls to action. In marches across the country, activists waved signs and gave speeches urging the government to canceling these proposed loggings.

A quick guide to timber industry terminology. “Thinning” is the process of intentionally cutting certain individual trees for the purpose of reducing wildfire susceptibility. While some controlled cutting, or “thinning,” of these trees is healthy and actually encouraged by experts, any more than necessary tips the scales too far. “Restoring” refers to the practice of planting trees in previously forested areas. Some conservation advocates, like Madeline Cowen of Cascadia Wildlands, are dubious of both of these terms: “These are greenwashed terms; they can be euphemisms for logging,” Cowen said.

But when applied responsibly, these practices can have huge benefits. “Protecting these forests from logging can work alongside thinning small trees in highly flammable logged areas, “said Forest advocate Dominick DellaSala of the organization Wild Heritage. “[This] would begin a process toward the President's goal of 30% of the nation's lands and waters protected by 2030.”

When we know where these elder trees are, we can work harder to protect them. The ideal outcome is protection in perpetuity. Hopefully, we can walk on the silent, pine-needle-cushioned forest floor, and the sound of chainsaws will be only echoes of the past.

What You Can Do: The months ahead will determine the success of The Forest Service’s new approach. Until June 20, Americans have the chance to send in comments and help shape this new chapter. Also this summer, the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management will host educational workshops to highlight sustainable stewardship of the plentiful pinyon-juniper ecosystems.