Though the art market doesn't always embrace them, environmentally-conscious artists ignite important conversations.

At a September exhibition in Paris at a private home, artist Morgane Porcheron showed me a faded Converse shoe spilling with seashells, rubble, and seaweed. This small work of art pulled me into a scene of forgotten belongings sloshing in the waves. I asked Porcheron what inspired this piece, and she launched into how she came up with the idea while strolling down the beach in Normandy. She accidentally knocked over a wooden board, causing the debris resting on it to spill into her old shoes. This piece was a tribute, Porcheron said, to what is rejected by the sea.

“With our planet burning, the power of art to sound the alarm … is more crucial now than ever,” –Stefano Vendramin

“With our planet burning, the power of art to sound the alarm, to light up new paths, and to mobilize us towards them is more crucial now than ever,” Stefano Vendramin, one of the exhibition's organizers, wrote in a catalog for the exhibition. Vendramin is a curator of art related to environmental themes and founder of STRATA, an artist agency that supports artists like Porcheron whose work he sees as furthering conversations about climate change.

Porcheron and Vendramin are part of a growing movement in Paris to bring ecological themes to the forefront of the contemporary art scene. While art such as Porcheron’s fuels climate discourse, she and other contemporary artists whose work considers climate issues often cannot rely on traditional means of selling their work. “If you’re not making artwork that you can hang on a wall, there’s very little market for it,” Vendramin said. Still, as the world grapples with the reality of climate change, artists and curators in this global art hub are creating a space for artists to help shape the discussion.

The climate crisis feels distant for many people, both in time and location, said Liselotte Roosen, an online clinical psychologist at Positive Mind Works, based in Australia and New Zealand, and Psycholoog Op Afstand, based in the Netherlands. But art can reduce that psychological distance, according to a study of Roosen’s, by evoking emotion and displaying personal relevance.

Three characteristics are crucial, she said, for art to resonate: It’s memorable, participatory, and personally relevant.

Three characteristics are crucial, she said, for art to resonate: It’s memorable, participatory, and personally relevant.

“Installation art is really good because it’s easier to have that immersive feeling or get that participatory element,” Roosen said. Installation art is mixed-media work that often involves sensory and spatial experiences.

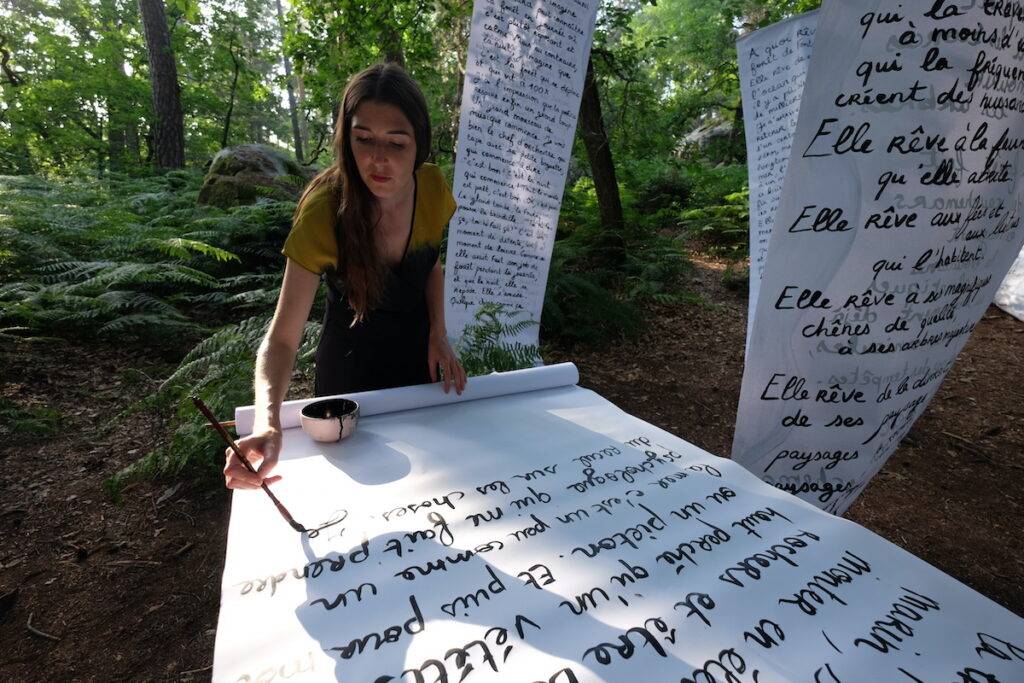

Carmen Bouyer, an ecological artist based in Paris, holds a participatory art installation about once a year. She held one such installation, “A quoi rêvent les forêts?,” in June 2022 in the Fontainebleau Forest outside of Paris, as part of the Nuits de Forêts festival. In the dappled light of the forest, large sheets of paper dangled from the trees. “What does the forest dream of?” Bouyer asked the group she had invited.

As participants answered, Bouyer scrawled their musings in inky calligraphy. Several hundred people gathered for the festival. Some shared stories and poems with her beforehand and others spoke their stories live.

To offer to the whole world / My trees, my pure air, / To take care of the living / And make it last, / This is my ultimate dream

–Babeth Aloy

“To offer to the whole world / My trees, my pure air, / To take care of the living / And make it last, / This is my ultimate dream,” Babeth Aloy, an artist who participated in the installation, wrote in her poem, “Rêves de forêt,” which she gave Bouyer for the event.

In the Converse sculpture and her other work, Porcheron contemplates how industrialized material confronts the natural world. She typically creates sculptures out of discarded construction site materials and plants. Another piece of hers, Tetris Végétal, consists of stacked cement blocks with plants growing through the crevices. “Tetris Végétal was born from a feeling of crampedness in big cities,” Porcheron said. “The plants are enclosed by these blocks. They seek the light and just want to unfold.”

Porcheron wants us to look down at the ground beneath us and consider our actions. “I would like viewers to become aware of their soil, its richness, its potential and possibilities,” Porcheron said. All human actions appear in the soil, including our waste and pollution, she said.

While Bouyer has received distinguished residencies and Porcheron has displayed her work in esteemed galleries including the Louvre, their work isn’t what most collectors seek.

“The challenge is to sustain a form of income and to keep doing the work in one place long term,” Bouyer said. Bouyer is not really in the art market, she explained, nor is she trying to enter it. She makes a living through accepting residencies, which pay her to do place-based work. She also organizes events for schools, galleries, and environmental organizations.

“Very few collectors are willing to buy artwork which they cannot envision in their living room,” Vendramin said. Another factor, according to Vendramin, is that these pieces are often not tradeable. Collectors might purchase art as an investment if they anticipate its value going up. But some forms of contemporary art, such as Porcheron’s installations using plants and soil, aren’t made to be kept for long periods of time and then sold to the next buyers. What’s more, Vendramin said, “They don't want artwork shouting at them about the environment.”

STRATA has launched a number of initiatives to support artwork that Vendramin sees as pivotal to society’s climate discourse but that may not appeal to collectors.

One of these projects was a two-week public art exhibition in June 2021, called Aparté #2, that Vendramin curated with Collectif Embrayage, the organization that founded the Aparté series. On the bustling streets of Paris’ Fifth Arrondissement, nine artists each displayed their work in the storefront of a different eco-responsible shop. One piece was a collage of receipts, a comment on our consumption habits. Another featured flowers floating in vases and fastened to fishing weights. The artist, Arthur Guespin, intended the flowers to appear suspended in space and time, as if plucked from the cycle of degradation that occurs with the commodification of living things.

The art featured in Aparté #2 is exactly the kind of work Vendramin said he wants to support and thinks will make an impact. “I just want to help these artists who are making this work that they maybe cannot sell in galleries,” he said. A crowdfunding campaign paid the Aparté #2 artists for their work.

Vendramin is also working with Art of Change 21, an organization founded by Alice Audouin, a curator and specialist in sustainability and art, that holds installations at the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP) summits, to get the public involved in creating climate-related art.

One of the organization’s projects, called Maskbook, invites people at the climate summits to use waste materials or scavenged items to make masks.

“Maskbook raises awareness and mobilizes the public through creativity using the anti-pollution mask,” the Art of Change 21 website says. Over 7,000 people from more than 40 countries have participated so far.

“COP is very dry,” Vendramin said. “We hope that by inviting artists there we can change the discourse.” And they’re not just there to pressure government officials. They are out on the streets, galvanizing the public through participatory works.

Maskbook made an appearance at COP27 in Egypt in November 2022. “We had lots of people stop to look at the exhibition,” Vendramin said. “I think we stood out because of our artistic content, which is still fairly rare at COP.” After the exhibition, about a dozen participants from places such as Zimbabwe and the U.S. gave Vendramin their contact information and expressed interest in hosting a Maskbook workshop in their own countries.

A significant motivation for both Aparté #2 and Maskbook was bringing climate-related art to audiences that wouldn’t see it if it were in a gallery. Located in businesses on heavily trafficked streets, the Aparté #2 installations reached people who were not necessarily looking for climate-related art. Vendramin estimated that 5,000 people saw these works during the two weeks they were on display. “If we put this in a gallery we would have had a few hundred people at most,” he said.

Similarly, projects like Maskbook or Bouyer’s participatory installations, which she advertises to the public, break out of gallery confines, extending the conversation beyond a few elite art collectors.

“I think it’s really important that this type of art is free and that it’s in a public space,” Roosen said.

While climate-related art can get the public thinking about climate change in new ways, Roosen suggested that viewers need to translate thoughts into action. One solution, Roosen suggested, is holding discussions. “When people come out of the experience, I think it’s important to have a space where people can sit and talk,” she said.

Aparté #2, for example, featured workshops and guided tours for the general public to supplement the exhibitions. While Vendramin said that it is difficult to measure the impact on customers who passed through these shops, he said the business owners approached him after the installation and shared that the artwork made it easier for them to talk with customers about their own climate commitments.

Roosen also noted that solution-oriented work is more likely to move people to action, as opposed to art that expresses more pessimistic themes. Artists, of course, are not known for avoiding the melancholic. Pair installations with documentaries or discussions to explore solutions, Roosen suggested.

As Vendramin and the artists he works with make space for artistic expression of climate themes, climate-consciousness is gaining traction in the broader Parisian art scene as well. In 2022, the annual Art Paris became the first art fair in the world to conduct a complete carbon life-cycle assessment, and one of the fair’s two main themes was “Art & Environment.”

Palais de Tokyo, one of the most renowned galleries in Paris, is gearing up for ecologically and socially-focused programming, such as “Reclaim the Earth,” an exhibition that ran for five months in 2022.

STRATA is making some changes to further influence climate conversations, with plans to make the connection between eco-responsible companies and artists central to its business model.

“The responsibility of the art world in terms of raising awareness and producing tangible ways of action is huge,” Bouyer said. “Here in France, rational, more scientific discourse is very dominant … but telling the story through more personal, emotional, complex ways through the arts is absolutely essential.”

Bouyer hoped that her Fontainebleau exhibition would remind participants that together they could heal the human relationship with the earth. She said there were a couple of people who were brought to tears by the experience and embraced each other.

Aloy, who has done some of her own work in the Fontainebleau Forest, said she saw the exercise as a warning to respect nature and recognize how fragile it is. “I learned a lot by going to the forest and feeling the connection as an artist — what I could give to the forest and what she could give back to me,” Aloy said. “When you’re connected to nature, you’re connected to yourself.”

“Sometimes we can only tell truths through fantastic stories,” Bouyer said. And when it comes to the complex truths of the climate crisis, those stories might even be told through a debris-filled Converse sneaker.