When their beloved river was threatened by plans for a dam, residents of a small town in Bosnia and Herzegovina fought back to save the Neretvica River.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), the Balkan rivers are an integral part of our geography and the reason why our region has been dubbed “the blue heart of Europe.” Our rivers are tied to our folklore and our understanding of ourselves: they’ve been used to divide us and to unite us, and we are raised to be both fascinated by their beauty and fearful of the freezing waters in their depths. We speak about our rivers as if they are old friends, and when they are threatened, those of us who live in this blue heart tend to take it personally. Which is why local residents in Buturovic Polje, a small village in the municipality of Konjic, BiH, felt called to action when they learned of plans to build fifteen small hydropower plants (sHPPs) along twenty-five kilometers (fifteen miles) of Neretvica, the river that runs through the village.

When Ibrahim Turak, a founder of a group that rose up to save Neretvica, sent me directions to help me find our meeting place, he said simply, “Buturovic Polje, we can meet at the gas station.” That these brief instructions were, in fact, thoroughly adequate, highlights the intimacy of this community and the familiarity of its landscape — the small size of an area where an action so large took place that it even grabbed the attention of Leonardo DiCaprio.

Ibrahim suggested we drink a coffee first, refusing to let me treat. “I became a grandfather yesterday; it’s on me,” he told me. “After this, I’ll take you on the tour, starting from where our picket line began” Ibrahim is one of six main activists who helped to form the movement known as “Neretvica — Pusti Me Da Tečem (NPMDT),” meaning “Neretvica — Let Me Flow.”

“If you grabbed a river by its neck, what would it say to you?,” Ibrahim asked me, and then he answered: “Let me flow. That’s why we chose it. To speak for our river, to speak for Neretvica.”

“It was a battle against corruption, not the country,” Ibrahim continued. He was referring to what later came to light: that two of the fifteen sites would be owned by the state electric company, who led the deal with the local municipality; the other thirteen would be sold off to private investors, behind closed doors.

While the use of sHPPs has been promoted as a more environmentally-friendly alternative to coal (currently the leading means of energy production in the country), local activists see this as a choice between two evils. “We’ve been in contact with the State Electricity company, to help them connect with locals and to seek the use of wind turbines instead,” Ibrahim tells me. “That’s what we’re working on now.”

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, hydropower energy has been growing in popularity, with more than 3,000 dam projects either proposed or in process. Of these, 91 percent are small hydropower diversion dams, whose “cumulative impacts often outweigh those of a single large dam,” according to a report. They’re changing habitats, altering the course of river waters, and leaving dry riverbeds behind. Through fragmentation, they’re hindering the ability of fish to move upstream, and they’re reducing the flow of water where once it was plentiful. What was once a beautiful, free-running stream becomes a desolate landscape.

When the struggle in Buturovic Polje began, it was 2006. Smartphones were not yet ubiquitous, and access to information depended heavily on word of mouth, especially in a village setting. Safet Saraljlić, another founding member of NPMDT, knew that a hydropower plant had already been built alongside the Vrbas river in Banja Luka, some 200 kilometers (125 miles) away. When news spread about the plan to construct dams alongside Neretvica, Safet grabbed his camera and a friend to document the effects of damming on the river Vrbas, to try and imagine what was coming to Neretvica. “Not a single drop of water was running at the bed of the river I arrived at,” he said, “not for three kilometers.” Safet returned with the pictures to Buturovic Polje and shared them with inhabitants, many of whom saw for the first time what might happen in their immediate community.

Safet’s photos triggered an awakening. Locals began to question whether hydropower would be as fruitful for their region as investors had made it seem, with their promises of jobs and further project opportunities in the region. In response to the same situation in Serbia, journalist Radmilo Markovic later wrote,“Not only are resources the local population depends on destroyed, but locals don’t stand to benefit at all — profits are funneled to investors, and the number of jobs created is negligible: through automation, a single person can run multiple small hydro plants at once.”

In 2006, over 200 locals signed a petition demanding that their voices and opinions be heard by the government during the early planning stages of the project. Unfortunately, the municipality ignored the petition, and, in 2009, with no public consultation, the municipality of Konjic and the state-owned electricity company JP Elektroprivreda BiH signed a deal, agreeing to complete construction of the fifteen small hydroplants by the year 2013.

Neretvica, it turns out, is home to two endemic species, and building an sHPP would put that rare marine life at risk. This became the first point that local activists emphasized, one that had been ignored by both the municipality and the Electric company.

As I watched Ibrahim fill an old plastic bottle from his car with water from a nearby stream, it was clear how much he valued that simple, threatened act. He had worried that, while the hydropower project might provide electricity, it might also give these companies rights to the water. NPMDT’s activism wasn’t just about preservation, he stressed; it was also about access to clean drinking water. To strengthen their cause, NPMDT’s leaders reached out for support to several other local associations, including hunting, agricultural, and cultural heritage associations. Together, they formed a powerful coalition and used their respective channels to activate and inform the people of the region, most of whom lived (and still live) in small villages surrounding Neretvica.

With some digging, the NPMDT team discovered that in Bosnia and Herzegovina, projects like the one proposed for Neretvica must be approved by the EU’s environmental commission before construction can begin, specifically if funds are given from inside the EU’s banking system. In this case, an early inspection had indeed taken place, and the commission had produced feedback: Neretvica, it turns out, is home to two endemic species, and building an sHPP would put that rare marine life at risk. This became the first point that local activists emphasized, one that had been ignored by both the municipality and the Electric company.

Next, Ibrahim and his fellow comrades found a valuable ally in Aarhus Center, , a national citizen’s association that provides free legal aid to individuals, informal groups, and citizen associations. Together, they launched a series of appeals that halted construction attempts and revoked several building permits. Years passed with no further action by the hydropower consortium. The community began to wonder, would the construction of the mini dams still happen? But when machinery appeared again in 2020, Safet Saralijic made himself into a one-man blockade, which slowly attracted other community members and led to the formation of a Facebook group, now with about 7,000 members, that acts as the main site of information dispersal. What was once the concern of a few had turned into a movement of many.

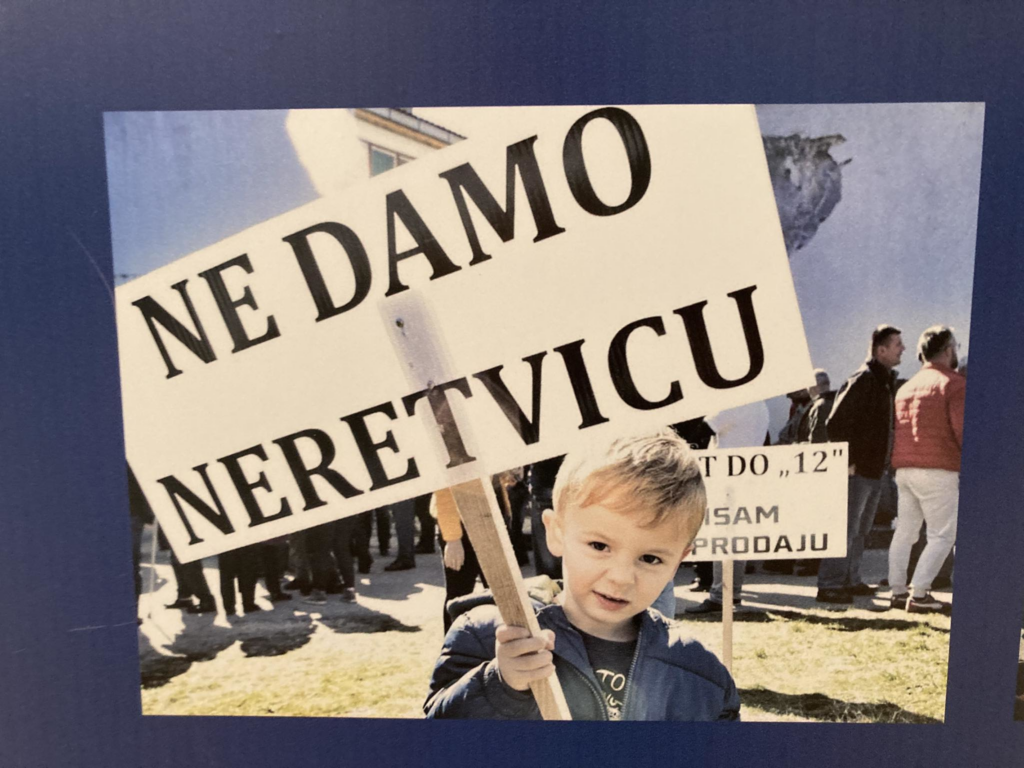

On February 22, 2020, just ten days after the creation of the informal Facebook group, the first protest at the local elementary school took place, with more than 1,500 people in attendance. The protest succeeded in spreading the sense of urgency that the group knew was needed to save Neretvica. The group’s internet visibility alerted both local and international media, and reporters’ subsequent presence at the protest led to a huge magnification of what was happening in Buturovic Polje. “We were being approached by several international organizations, asking what we needed to win,” Ibrahim said.

Their protest halted further construction attempts, and it wasn’t until several months later that a half a dozen workers from Amitea D.O.O., the construction company hired for the project, appeared and began digging holes for signs that would mark the construction area. At first, Safet was the only activist on site, but before long, he was joined by some fifty others.. Their goal was to delay the start of construction while the Aarhus legal team moved forward with cases regarding the ignored EU commission report and the fact that the initial building permits had expired. “We needed time,” Safet explained. “You know how painfully slow our judicial system is. We just needed the legal investigation to finish before they came here to build.” On May 19, the construction workers peacefully returned to Mostar.

Just over a year later, on June 14th of 2021, when construction workers arrived again, another protest took place, gathering over 700 people, including the popular band Dubioza Kollektiv. The protest made clear that the community had had enough. “We were truly ready for anything, arrest, even death,” Ibrahim said. “We had people here who were ready to give their lives for that river.” T-shirts and banners proudly highlighted the slogan, “VODA ILI KRV” (“water or blood”). “It was meant to intimidate, yes, but it also had a double meaning. They’re both intrinsic to our survival,” Ibrahim explained. “We had activists everywhere, hidden on the sidelines with Molotov cocktails. Both children and the elderly were present, all neighboring residents who believed in the importance of our river.”

Photos from that day testify to the solidarity and strength of the community. In numbers, they felt powerful. And while violence wasn’t the desired approach, people were impatient with the lack of clarity about their community’s fate, which led to a, “no means no, by any means” approach. That day, their blockade succeeded — Amitea D.O.O. again ordered their workers to retreat, and the legal battle over building permits continued.

Over the next two years, while various appeals were being decided in court, NPMDT placed a tiny metal container home on a small bridge entering Buturovic Polje. Activists manned it 24/7, allowing them to prevent anyone from Amitea D.O.O. from entering the proposed construction area.

A year into waiting, Safet had a thought: According to the regulatory commission for energy in the Federation of BiH’s website, Energetski Saglasnost (meaning Energy Consent) is, “a document issued by the Federal Ministry of Energy, Mining, and Industry, for which an investor or a qualified producer submits an application in order to acquire the right to incentives for the production of electricity from renewable energy sources.” Safet wondered: Did the state electric company ever even receive (energy) consent for this project? It was so simple — crazy, even — because energy consent provided the basis for the entire project.

“I just had this feeling something was missing,” Safet said. “I called all of our partners, the law team that was helping us, team members with boxes of papers, [and] no one could find the energy consent that they, the state electricity company, should have applied for, and that consequently should have been approved.” NPMDT filed a request to the federal ministry, and the Ministry’s response revealed that no permission had been formally granted to the state energy company leading the construction project. Safet’s instinct had been correct.

And that was it — the key to an eventual win for Neretvica.

“They tried to threaten us, to tell us they would sue our municipality for the millions they lost on this project if we continued to stand in their way, to lead us all to bankruptcy,” Ibrahim explained. “They tried to turn our people, the members of our community, against us, as if we would be the reason for … the fall of our region.”

In May 2023, an official statement sent to Ibrahim, Safet, and the rest of the NPMDT team put it in print: the contract between the state JP Electric Company and the Municipality of Konjic was terminated. No sHPPs would be built on Neretvica — not one of the fifteen originally proposed. A long battle over, the river was at last left to its natural purpose — to flow freely, without barriers.

“We returned the river to the people, but it wasn’t over for us. [Now] we wanted to return people to the river,” Ibrahim said. The movement decided to create fifteen recreational bathing sites alongside Neretvica river, as an alternative to the fifteen proposed sHPPs. “We wanted to create spaces where youth and others would connect with this river like we did, to value it and not let it be sold,” Ibrahim said. He proudly showed me two such sites, cleaned up and offering visitors wooden canopies for shade, stone ovens for cookouts, rocky beaches, and even a zip-line, all allowing people to enjoy the river and its beauty.

In addition, the group restored an old grain mill powered by the river and convinced the owners to allow one of two rooms (formally home to the mill owners) to become a museum showcasing the group’s successful fight to protect the river. Today, the room stands as a testament to their accomplishment, a living time capsule showing what happened and how they won.

How does a person stay committed to a story seventeen years in the making? Between 2006 and 2023, children were born, members of NPMDT left and joined. “If you really want to be an environmental activist,” Ibrahim says, “you can’t ever give up. You have to be sure you’re right. And for us, when defending the right to drinking water, one is never wrong. Nothing, not even the possibility of jail, should scare you.”