Students at a Waldorf high school in Western Massachusetts become onsite farmers — and participate in all aspects of agriculture.

Some of my most vivid memories from Hartsbrook School, which I attended from 1990 to 1998 (from first through eighth grade), are of trips to Brookfield Farm. The farm was just down the road on the border of Hadley and Amherst, Massachusetts. A trip there meant dirt beneath my fingernails from picking carrots and a brow glistening with sweat. I’d follow along after the Robbs, who owned the farm, eager to please and show that I didn’t mind getting dirty if it meant cuddling with a chicken or petting a goat.

What a privilege it was to experience the earth and animals in such a way. Living in Boston, Los Angeles, and now London, I see how many students’ only outdoor experiences involve concrete playgrounds. The Hartsbrook School — part of a network of 130 Waldorf schools across the United States — focuses on whole-being learning, connecting the mind, body, and spirit through early education. And much of that pedagogy involves a deep respect for, and understanding of, nature. During school days, we regularly hiked the Seven Sisters mountain range behind the school, chopped our own wood to whittle it into salad spoons, and spun wool from the sheep in the surrounding fields.

Recently, Paule Sustick, assistant director of the Land Stewardship Program at Hartsbrook, was holding a cucumber harvested from the onsite farm, when a 5th grader from Hartsbrook’s community after-school program wondered aloud, “Wait. What are we doing?”

Sustick reminded the child that they were going to make pickles. “Don’t pickles just grow on vines?” the child asked. Cucumbers grow on vines, Sustick explained, and pickles are made from them. Sustick calls this “a beautiful aha moment,” when students realize they can transform this thing grown in their garden “to the thing that would end up on their hamburger. I saw that shift in how they see their food and how they see what a farm is and what it does.”

Since 2017, Hartsbrook has been incorporating a land stewardship program called ACTS (Agency, Community, Terra, and Social Justice) into their high school curriculum. Though I knew from my own time there that the principle of the program had permeated Hartsbrook already, the school created ACTS to enable high schoolers to learn more about the climate crisis and help find solutions.

“To me, it felt like some sort of hope [we could give our students],” says Sustick, “that they could affect change and be involved in some way.”

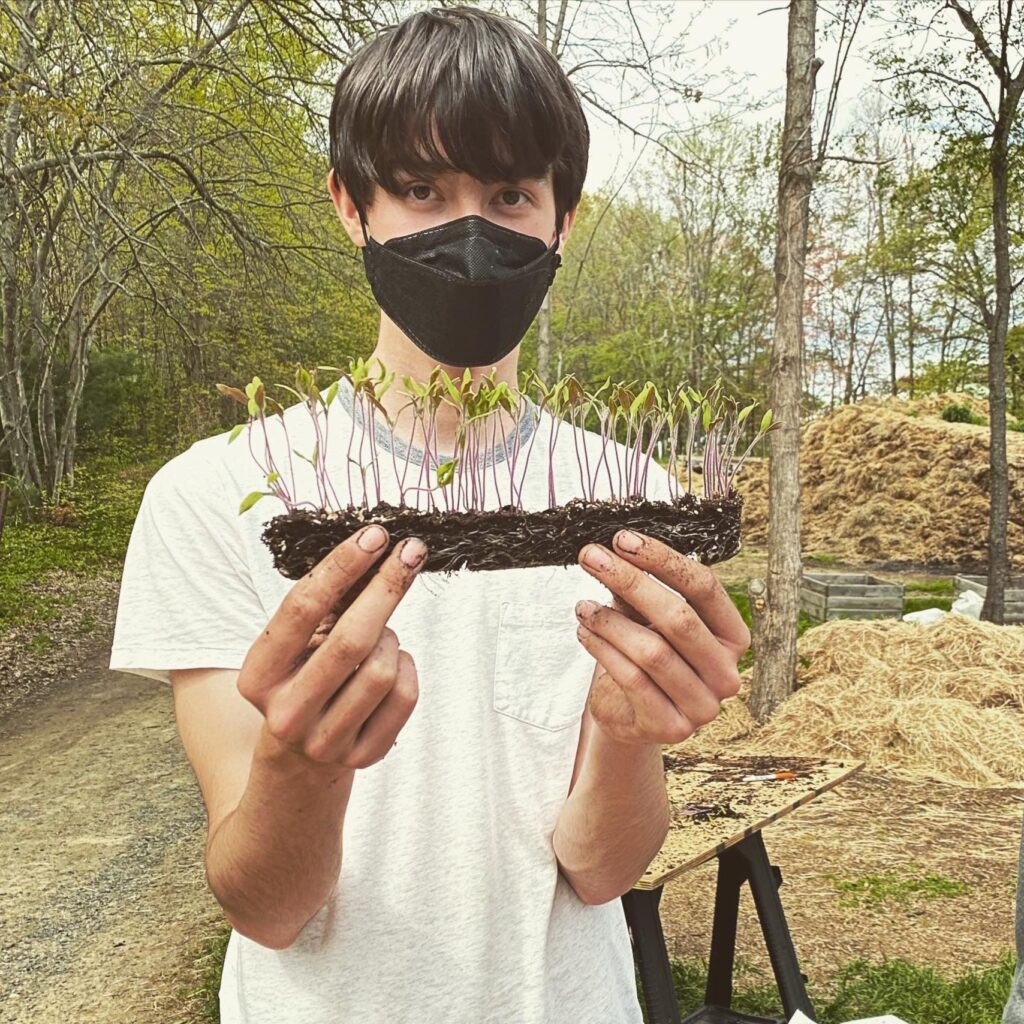

ACTS has seen a few iterations and is now focused on project-based work on Wednesday afternoons on the school’s nearly forty acres, which includes vegetable farmland and a small barn that houses sheep, goats, chickens, donkeys, pigs, and cows. Students participate in fence building, vegetable farming (seeding, growing, and harvesting), barn repair, land management, animal care, and more.

During COVID, when only Sustick and my old farmer friend, Nicki Robb, who developed the ACTS program, were able to complete hands-on farm duties, food justice became a central focus for the students who were learning through Google Classroom. Food justice is a movement that looks to rectify the inequality of access to fresh and nutritious foods. Hartsbrook began its own food justice journey by expanding its programs into the wider community. The Gray House, a non-profit organization in Springfield that provides food, clothing, and educational services to thousands of local families, is Hartsbrook’s newest ACTS partner.

“This new vision of what ACTS can be post-COVID involves [field trips], bringing speakers in, us going out to speak to others. We can go see what’s happening in other communities near us. We now have Gray House students come to us once a year,” says Sustick. “And we hope that will only grow.”

Because of ACTS, fourth graders come to groom the animals on a regular basis during the school week. Over the years, especially during the last decade, Robb says she has observed an increase in anxiety, nervousness and overstimulation in the children. “Grooming these animals, having that lovely experience of tying up a donkey, working with a curry comb, brushing, you can feel in the child a kind of a settling down,” Robb says. “[We get the children] to use their bodies [with] hauling buckets of water, bales of hay for the animals. “[And I see a] lovely new rhythm that settles into them.”

Getting to a place where ACTS was a formal part of Hartsbrook’s curriculum has been a long journey that began in the 1980s, when Robb, her husband Ian, and David and Claire Fortier started Brookfield Farm, a 120-acre vegetable and livestock farm. Robb’s two sons were there from the beginning as well, with her eldest in Hartsbrook’s inaugural first-grade class in 1985. The Robb family connection to Hartsbrook was partly the impetus for seasonal visits from students to Brookfield to join in planting and harvesting chores, all of which fit into the Waldorf pedagogy.

During the 1990s, Robb simultaneously worked at Hampshire College for fifteen years, running the Hampshire College Farm Center. The more involved she became in connecting those two communities through her own farm, it was clear to her that land stewardship needed to be incorporated into the Hartsbrook curriculum across all grades.

“This needed to be a slow journey of growth,” says Robb. “We didn’t want to take on too much too quickly, [but] it was becoming clear to us that the students, the children, needed to be able to offset the drive towards technology, [that we needed] to give them more hands-on experiences of working with a natural environment, especially as seen in a farm setting.”

Robb left Hampshire in 2008 to focus full-time on Hartsbrook. Four years later, through a generous land donation under the Agricultural Preservation Restriction Program (APR) from founding Hartsbrook parents Alexander and Olivia Dreier, the school acquired the 33 acres of land that is now the heart and soul of ACTS. With the farmland and small barn acquired from the Dreiers, more and bigger animals were brought in, and by 2018, the Land Stewardship Program was officially implemented.

Currently, The Hartsbrook School’s high school students are focusing on food systems — everything from soil quality, growing, and harvesting, to food distribution and the worldwide issue of food waste. Because there are only forty students in the high school, they’ve been able to visit various local farms and distributors on a regular basis. For each topic, the students generate their own questions, record the answers, document their visit with photos and note-taking, and then present what they’ve learned. They also have speakers come in to discuss permaculture, biodynamic farming, and other topics relevant to food systems.

“All of this is to generate ideas for them around where food growing and feeding ourselves has come from and where it’s going,” says Sustick. “Questions around lab meat came up in one of our conversations; questions around GMOs, microplastics, and forever chemicals have been asked. These are all things that the students have brought up that they want to know about.”

Waldorf education has always championed a holistic view of ourselves in the wider world, and Robb feels that ACTS is a good fit with this view, since it incorporates both social justice and environmental stewardship.

“This has taken on a new sense of urgency with not only our climate crisis, but also our sense of disconnect from one another,” says Robb. “We have the ability to be intellectual and academic in our thinking; we also have the ability to cultivate our heart capacity through relationships; and we have the ability to actually do something. With the combination of those three parts of what it is to be a human being, we feel that we are essentially educating the whole student. [ACTS] is a culmination of [that].”