Two Rhode Island projects show that investing in sustainability pays off for everyone.

Standing on the sidewalk at Sandywoods Farm in Tiverton, Rhode Island, you’d never know that the community was at the cutting edge of sustainable affordable housing when it was built in 2011. It simply looks like a rural neighborhood of charming houses, with kids playing in their yards and adults heading inside to prepare dinner.

But underneath this stereotypical suburban setting lies a strategy of long-term climate resiliency mixed with affordability that has been gaining momentum over the past decade in Rhode Island. Housing is considered affordable when it costs no more than 30 percent of the occupant’s gross income. There are not enough affordable units across the country, due to skyrocketing real estate prices and mortgage interest rates, along with deflating inventory. But the Sandywoods project redefined what affordable housing looked like and how it was designed from the inside out, so much so that its Union Studios design team in Providence has since initiated or completed six additional sustainable affordable housing developments in the state. More are in their pipeline, highlighting a growing interest in these types of developments, even in the face of increased up-front construction costs.

Beginning with small footprint designs, the units each feature electric air-to-air heat pump heating and cooling systems, an on-site wind generator that offsets most of the residents’ utility costs, and thick, wet-blown cellulose insulation that seals out air and often has more recycled materials than traditional fiberglass. These ingredients have contributed to reduced car use and energy savings, and have galvanized the community around its shared mission of sustainable living with a decreased price tag for residents.

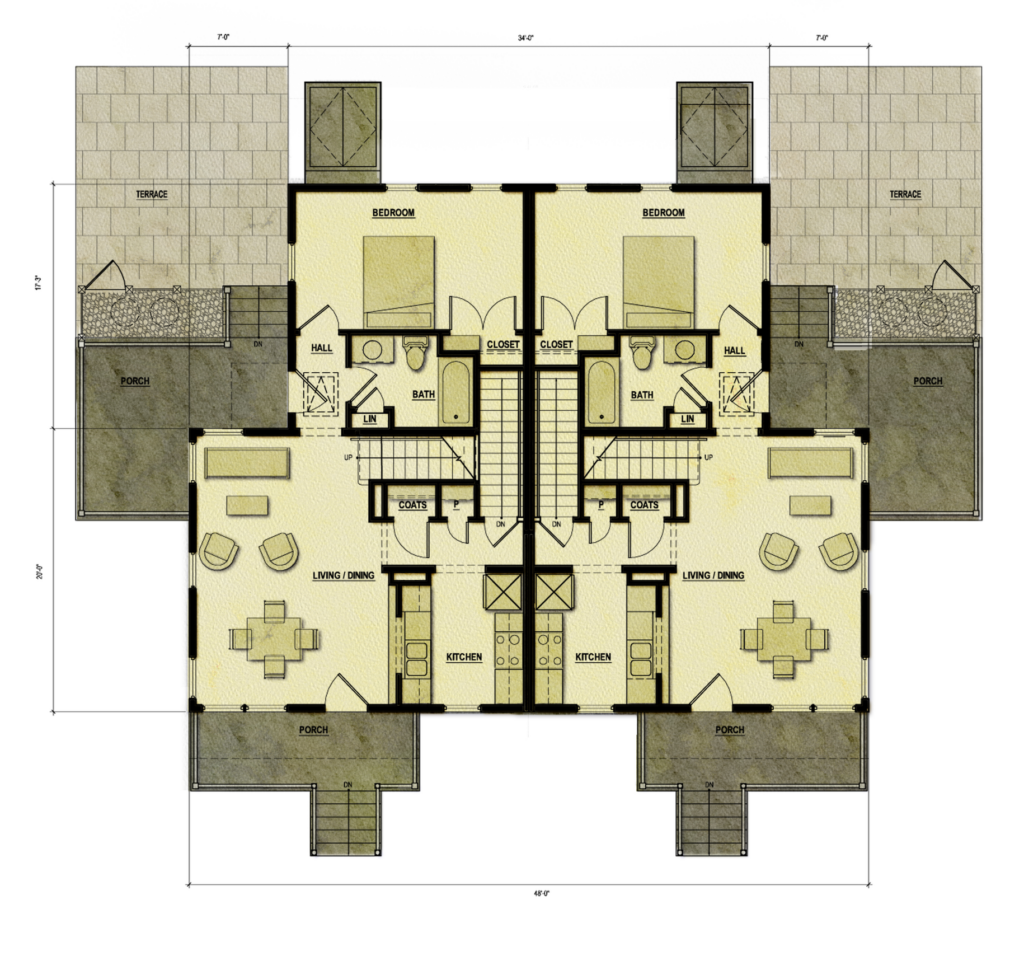

Sandywoods’s fifty affordable rental units are a mix of single-family homes, duplexes, and mixed-use buildings, surrounded by community gardens and land conserved by The Nature Conservancy. Rental fees fall within the fair market rent and income limits provided annually via the Office of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — $1,398 a month for a one-bedroom apartment. Beginning with small footprint designs, the units each feature electric air-to-air heat pump heating and cooling systems, an on-site wind generator that offsets most of the residents’ utility costs, and thick, wet-blown cellulose insulation that seals out air and often has more recycled materials than traditional fiberglass. These ingredients have contributed to reduced car use and energy savings, and have galvanized the community around its shared mission of sustainable living with a decreased price tag for residents.

The challenge was — and remains — economics, says Paul Attemann, principal at Union Studio Architecture & Community Planning in Providence, R.I., which designed Sandywoods with Newport, R.I.-based Church Community Housing Corporation (CCHC), a nonprofit affordable housing developer. Designing and building sustainably is expensive, and affordable housing is constrained by available funds, he explains. As much as the client and developer want to achieve sustainability objectives, “some goals must be reevaluated when pricing comes in, and the cost of construction and supply chain needs become the driving force of decisions and concessions that the developer has to weigh,” he says. “It’s a tight balance and something that evolves from the beginning. Economics is definitely a factor in how sustainable a project can be.”

But Sandywoods was an experiment that demonstrated that this kind of community planning and sustainable design was achievable with affordable housing, says Douglas Kallfelz, managing partner at Union Studio.

“Sandywoods set the stage for what is possible. It was perhaps the earliest demonstration in Rhode Island that this level of sustainable design was possible in the realm of tax credit affordable housing,” Kallfelz says. Since the completion of Sandywoods Farm he says, “sustainable practices and a focus on energy efficiency have become not only an expectation, but in many cases, a requirement of our affordable design work.”

Union principal Joe Haskett adds, “There is a trend toward sustainability in affordable housing. Look at the economics behind it. We have a quasi-public/private agency in Rhode Island Housing, and they have incentivized sustainability through their Qualified Allocation Plan. They say ‘if you can do this, we want you to do more sustainable design.’”

And that’s what’s happened. Union has developed multiple sustainable affordable projects across the state and region, including in East Greenwich and Providence, R.I., and in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Its 54-unit West House II senior housing complex in Middletown is under construction now, with nearly $18 million in grant funding from RIHousing, including funds from the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, enabling the project to meet the passive house standard of energy efficiency.

Featuring solar panels to provide power, efficient heat pump systems for heating and cooling, and an airtight building envelope that restricts heat loss (or what’s called thermal bridging), the complex will consume less energy than a conventional building, and reduce carbon emissions, says Christopher Chutz, a project manager at CCHC. It also is being constructed on the site of a former parking lot, he says, so there will actually be less impervious surface after completion than there was before, which is a boon for rainwater management in an era of increased flooding from storms.

“It's more efficient in the sense that, over time, with this type of building envelope, the air exchange between the inside of the building and the outdoors is minimal. And then when using the higher efficiency heating and cooling system, the amount of energy over time that it takes to heat and cool the building is significantly less,” Chutz explains. “So as far as the costs, typically, there is a 1% to 4% premium to do all of these upgrades. But then over time, the energy bills are going to be much lower.”

These two projects, one old and one new, both exemplify how longevity is driving decision making. It costs more to design, develop, and build with a view to sustaining cost savings in the future, but those savings, along with the climate impact (including reduced greenhouse gasses), as well as the added health benefits due to improved indoor air quality, make it more than worthwhile in the long run.

All of these advancements in sustainable building practices benefit Marika van Vessem, a Sandywoods resident for 13 years and former art gallery owner. She’s grateful for her comfortable and private one-bedroom duplex with a garden and patio. Utilities are included with her rent, so while she doesn’t notice cost savings there, she says sustainability is important to her and many people that live there.

“I love living here, (with) many wide-open spaces and easy connections to surrounding areas,” she says. “I chose to live here as I was a working artist at the time and the community promised many benefits and spaces to work. My living needs are totally met.”

Haskett notes that energy-efficient, utilities-included rentals like van Vessem’s are helpful to people who might otherwise experience “utility poverty” — the situation that results when people who qualify for affordable units based on a percentage of median income still struggle to pay utility bills. So, designers’ goals are to bring down energy costs for the owner and tenant by increasing the quality of construction, including specifying more durable materials, which helps the tenant, the lender, and the community.

Indeed, Kallfelz has observed increasing numbers of developers in the affordable housing market who are pushing for the kinds of sustainable practices that have previously been considered achievable only by market-rate, for-profit developers. Chutz agrees that the affordable housing industry is a leader in the high-performance building space, particularly in large states like Massachusetts, California, and New York, where additional funding sources for energy efficiency improvements can be more accessible.

Going forward, Chutz says that thanks to changes to the Rhode Island building code introduced in January 2024, “many of these sustainable building elements will become commonplace.”

“This speaks to timelessness and longevity and durability of housing. It’s something we think about in all of our projects — how can they be sustainable and useful over the long term?” says Union Studio’s Attemann. “It’s not just solving an immediate housing crisis or critical need, it’s our long-term vision of creating quality, economical, and comfortable homes. Sandywoods was the first stepping stone that established the path forward for more opportunities.”