As India deals with deadly extreme heat, urban planners try to turn down the temperature.

On May 22, 2023, the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) sounded the alarm for heatwaves in New Delhi, along with its neighboring states, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana. In certain parts of the capital city, where over twenty million people reside, the mercury surged past 45°C (113°F), marking one of the hottest days of the year. The IMD reported that 2023 experienced the warmest February since 1901, with the maximum temperature soaring to 29.5°C (85.1°F).

India is the fifth-most vulnerable country when it comes to extreme weather events and climate change, according to the Global Climate Risk Index. Between 2011 and 2018, India experienced an estimated 6,187 deaths attributed to heat stress. The country’s rapid urbanization has created increased construction and pavement, exacerbating high temperatures. And densely populated areas lack adequate green spaces and vegetation — essential for cooling.

But some urban planners are working to build cooling into design — prioritizing green spaces, urban forests, and tree-lined streets, along with vertical gardens, green roofs, and community gardens. “Communities are coming together in tree planting and heat-resilient projects to build a collective sense of urban responsibility,” says Amit Khanna, urbanist, educator, and design principal of AKDA. She points to Delhi's central area around the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) as “a remarkable example for its use of green space to cover the berms and reduce the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect.” AIIMS compensated for its own 2022 redevelopment project by planting 26,410 saplings.

It’s important to boost awareness among residents about UHIs and their impacts, Khanna says, and to invite their participation.

Temperatures in many cities and suburbs are usually hotter than in nearby rural areas, by as much as 4°C (7.2°F) than in the surrounding countryside, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. To address this urban heat, a social enterprise in India is tapping trees, which have a remarkable cooling effect. They “cool down the air by releasing water vapor through their leaves [chilling] the nearby atmosphere,” says Vikas Puthran, Head of Projects at Grow-trees. Tree shade reduces the heat absorbed by buildings and roads — with shaded spots being up to 10-15°F cooler than sunny areas. And trees clean the air and reduce noise, explains Puthran. “When you put all these things together,” Puthran says, “they can make the city cooler and more comfortable.”

Grow-Trees has teamed up with various corporations for their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives. “In its fourteen years of operations, Grow-Trees has planted more than eighteen million trees in twenty-three states on public lands involving residents,” Puthran notes. Its project called “Trees For Delhi” aims to plant a total of 180,000 trees in several densely populated areas of the city. They’re roughly halfway there. “These trees were planted at seven different locations across the city, including a wide range of open land, river banks, public parks, and other types [of environments],” he says. “Trees for City,” is ongoing in Jamshedpur — the most densely populated city in the state of Jharkhand. There, Grow-Trees has a target of planting 12,000 trees in mini-forests. “Planting trees in the urban areas around Jamshedpur could expand forest cover by nearly ten acres, improving the overall air quality and ecosystem,” Puthran states.

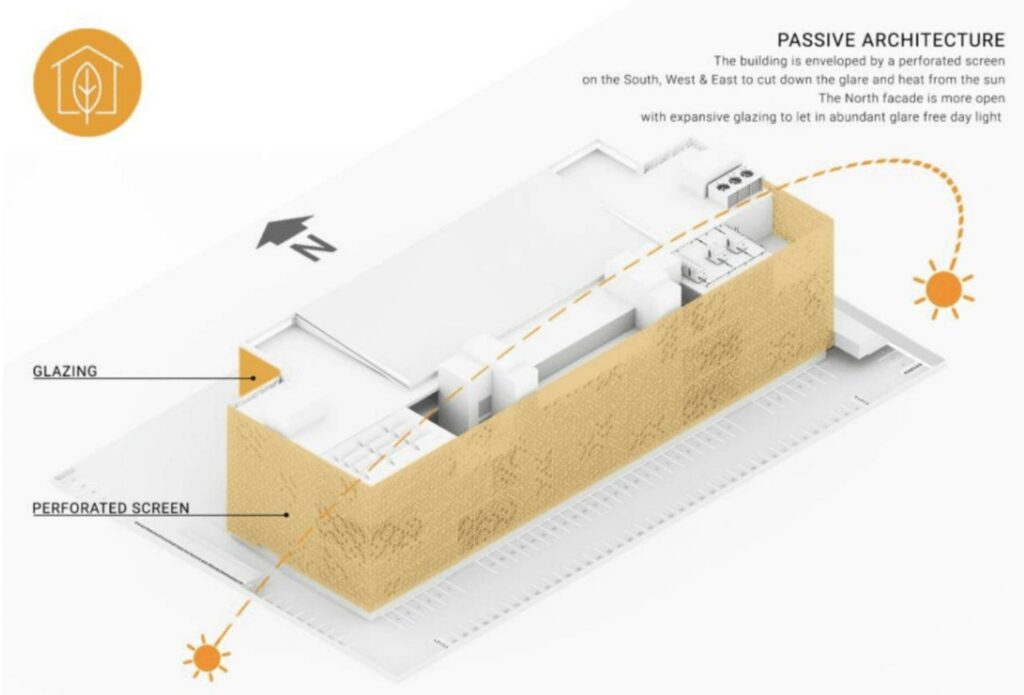

IMK Architects — an architecture and urban design practice founded in 1957 — is another organization active in combating city heat in India. One of their recent projects is the AURIC Hall in Aurangabad — a roughly 55,000-square-foot building designed “to stay cooler,” says Rahul Kadri, IMK Architects partner and principal. The architects covered the entire roof with highly reflective materials. “We used a distinctive net screen made of aluminum, inspired by the motifs used in traditional Mughal architecture,” Kadri says. “This helps minimize solar heat gain and controls airflow through the building, regulating internal and surrounding temperatures.” In addition, multiple two-story, green pocket terraces on the building’s southern side minimize heat gain.

The company collaborated with organizations to design and build the Malabar Hill Forest Trail — an elevated wooden walkway in one of Mumbai's last remaining natural ecosystems. “Our aim is to preserve and restore degrading urban forests,” Kadri says. Urban forests offer shade, help to cool through evapotranspiration, absorb heat, and improve air quality.

India will continue to face deadly temperatures in its cities. But these collective efforts focused on urban forests, as well as sustainable design are a step toward turning down the temperature.