As climate change threatens coastal communities, a neighborhood in Newport, Rhode Island, works to preserve a part of the nation’s architectural heritage.

Kayakers in Newport, Rhode Island, are a familiar sight, lured by the pristine coastline and hidden coves of this historic coastal community. But kayaking through the heart of downtown, along roads lined by centuries-old buildings and residential homes, tells a decidedly different — and worrisome — story. When Superstorm Sandy ravaged the City by the Sea in the fall of 2012, water flooded a number of city streets and damaged many homes and businesses. A few intrepid kayakers decided to explore.

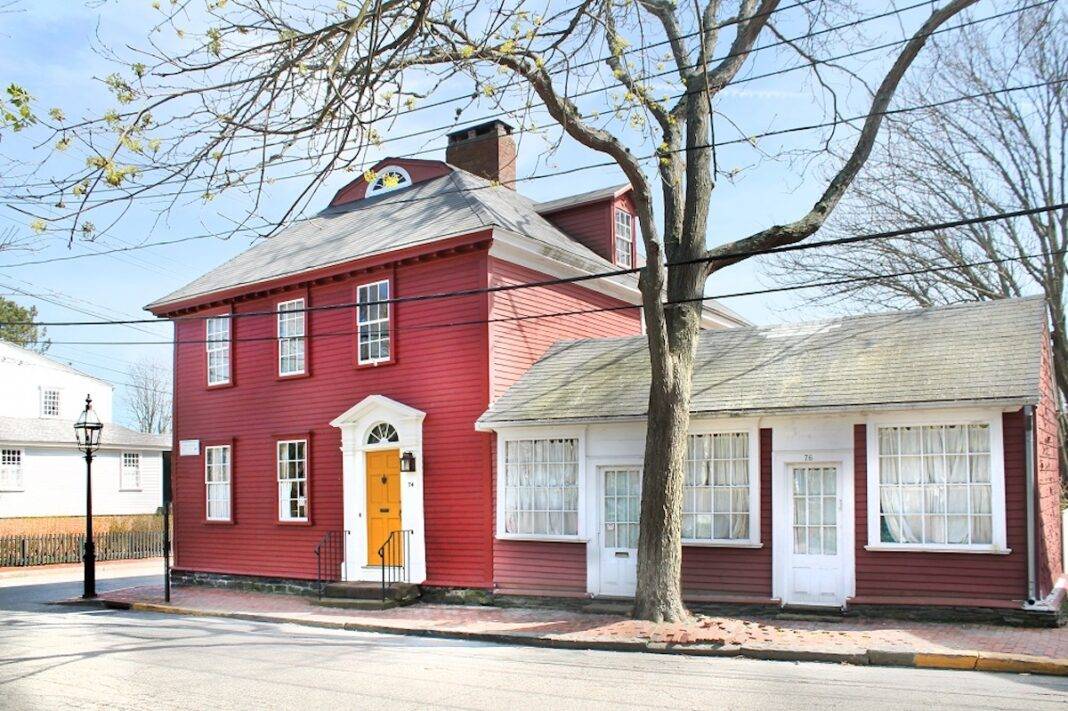

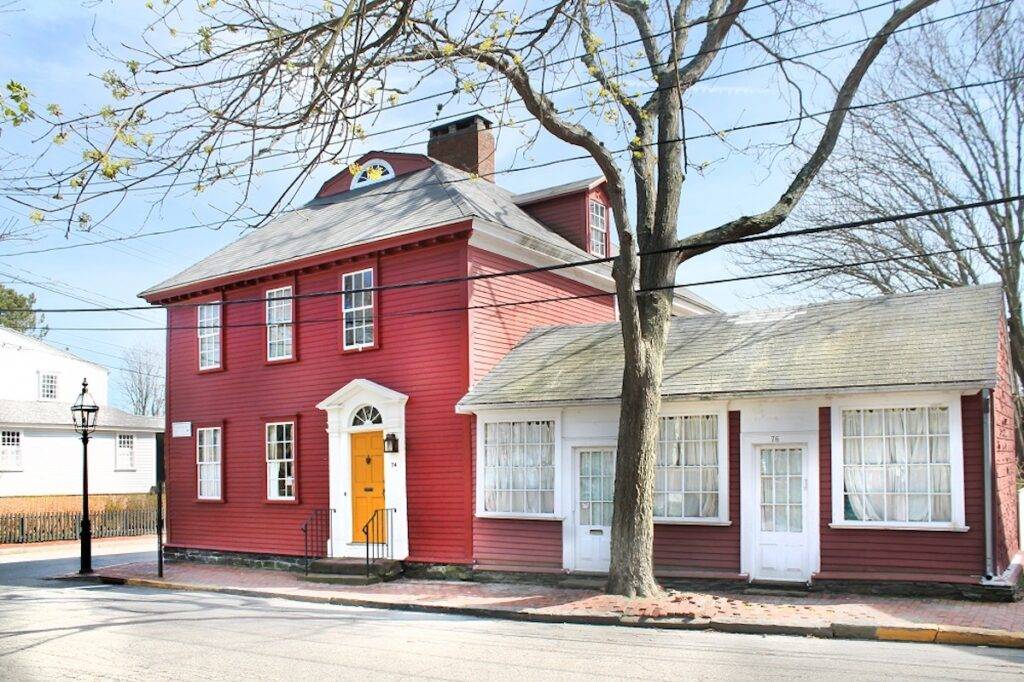

Known for having the largest concentration of 17th- and 18th-century homes in the nation, The Point pre-dates America itself. Homes that dot the harborfront neighborhood's tree-lined streets showcase every period of American architecture.

When Sandy moved up the Atlantic Coast, it left behind a trail of devastation. In the Ocean State, destruction included demolished structures, toppled trees, swaths of debris, standing floodwater, widespread power outages, and severe coastal erosion. One of the hardest hit neighborhoods, The Point in Newport, is also one of the state’s most historically significant. Known for having the largest concentration of 17th- and 18th-century homes in the nation, The Point pre-dates America itself. Homes that dot the harborfront neighborhood's tree-lined streets showcase every period of American architecture. Now, as climate change increases the risk of rising seas and more (and more severe) storms, residents and stakeholders here must find ways to both protect their homes and preserve a neighborhood that is a monument to the city’s (and nation’s) architectural heritage.

More than seventy-five historic buildings here are owned by the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF), an organization founded in 1968 by the late philanthropist and preservationist Doris Duke. Dubbed “the richest girl in the world” when growing up, Duke, who spent considerable time in her family’s Gilded Age mansion just three miles from The Point, oversaw the NRF’s restoration of more than eighty 18th- and early 19th-century buildings in and around Newport at a time when the city was scrapping such properties to make way for tourism development. (Another well-known preservationist with Newport ties, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, was a friend of Duke’s, and one of the foundation’s original board members.)

Today, The Point's biggest threat isn’t development, but climate change. Extreme high tides and coastal flooding due to accelerated sea level rise pose serious risks to the future of this and other low-lying historic communities.

Today, The Point's biggest threat isn’t development, but climate change. Extreme high tides and coastal flooding due to accelerated sea level rise pose serious risks to the future of this and other low-lying historic communities. During Superstorm Sandy, Narragansett Bay, New England's largest estuary, measured four to six feet of storm surge, leaving the foundations of many homes underwater, not only in The Point, but also in the neighborhood known as the Fifth Ward (located on the southern edge of the harbor), and on Bowen’s Wharf — the heart of downtown known for its shops, restaurants and busy marina.

As the neighborhood’s largest stakeholder, the NRF convened a conference in Newport in 2016, Keeping History Above Water, bringing together preservationists, engineers, city planners, legislators, insurers, historic homeowners and other decision-makers from similar communities to address what can be done to protect historic buildings, landscapes, and neighborhoods from the increasing threat of inundation. ]

“It was a combination of NRF and the board being very interested in where preservation could meet this very present and very contemporary environmental issue,” explains Alyssa Lozupone, Director of Preservation at the NRF. Using The Point as a case study, the conference ignited important conversations and inspired an exchange of ideas. The foundation had initially intended the conference to be a one-time event, but it soon became apparent that the question of how to preserve history in vulnerable areas was being asked not only in a few coastal regions, but across the country and worldwide.

“From there, I think it just grew, and so the conference really has traveled all over the U.S., and it's now going to be international,” says Lozupone. Previous Keeping History Above Water conferences have taken place in Annapolis, Palo Alto, St. Augustine, Nantucket, Charleston, Salem, Norfolk and even landlocked Des Moines, Iowa, where climate change-driven extreme weather events have caused historic flooding. The next two gatherings, both scheduled for 2023, will be held in Trinidad and Tobago and in Portsmouth, NH.

“It has grown geographical legs while the conversation at the conferences has evolved,” says Lozupone. “In 2016, it was still kind of novel, [but] now, it is accepted that yes, sea level rise is happening; we are seeing the effects, and now the conversation has evolved more into examples of what other communities are doing, and how we [can] take theory and put it into action. So it is becoming more and more actionable.”

A key component of the NRF’s mission has always been to ensure that its rescued and restored Colonial-era homes remain an active part of the community, not simply rehabilitated relics of the past. Museums have their place, but in Newport, where housing is scarce, keeping these buildings as dwellings has been the goal, and the foundation currently maintains more than seventy houses that it rents to “tenant stewards.” Whereas Doris Duke prioritized measures like updating bathrooms and kitchens to make the houses livable spaces in the 1960s, today, Lozupone says, “I think that very much means ‘how do we contend with the reality of flooding?’”

“The homeowner has a choice,” says Andy Bjork, chair of Newport’s Historic District Commission. “They either can continually pay a lot of insurance money and then repair every time water runs through the first floor … or we can do things to mitigate the flood.”

Preserving the architectural legacy of this little neighborhood within a 384 year-old city has been yeoman’s work. In The Point, “There are more than 100 homes that are [facing] flood risk,” explains Andy Bjork, chair of Newport’s Historic District Commission. He and members of the commission have been working to create design guidelines for people who want to elevate their homes, which is only one way to mitigate flood concerns. While some homes were marginally elevated following the hurricane of 1938 (one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history, according to the National Weather Service), elevation has, until recently, been left out of the conversation, at least when it comes to historic neighborhoods, where authenticity and aesthetics are sacrosanct. Bjork gets it. Some protective measures can end up modifying the aesthetic of a historic home, he concedes. “The homeowner has a choice,” he says. “They either can continually pay a lot of insurance money and then repair every time water runs through the first floor — and we may even have the risk of the building falling down or being abandoned and now we have lost the historic property altogether — or we can do things to mitigate the flood.”

Lozupone says the Historic District Commission has been a key partner in helping to tackle policy and education on the topic of sea level rise, flooding, and elevation in The Point and in Newport’s historic district more broadly. Turning ideas into action, the commission has collaborated with the NRF to create user-friendly elevation guideline graphics that will be released in the coming months. “[It’s] another way that we are trying to use our expertise to help educate the community on what they can do with their buildings,” she says. “We’re not the only property owners threatened by this, so it’s a multifaceted approach.”

In historic neighborhoods, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projecting continued increases in both the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, finding solutions is critical.

Remedial mitigation measures for historically vulnerable neighborhoods include landscape modifications and sandbagging around homes when storms approach. More complex (and expensive) alternatives include raising a home’s elevation or turning the basement into a cistern. Then of course, there’s relocation — moving homes to entirely different streets or neighborhoods, or even to other towns. (In 1890, a homeowner in neighboring Middletown moved his home, built 30 years earlier, via a barge across Narragansett Bay to Jamestown, where the property overlooks Newport to this day.) In historic neighborhoods, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projecting continued increases in both the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, finding solutions is critical.

Lozupone is hopeful. Keeping History Above Water, she says, often starts as a conference but ultimately becomes a catalyst for ideas and inspires other like-minded groups, organizations and agencies to tackle climate change and preservation challenges together. Solutions, she says, needs to come from the community. “So we like to think we come in, serve as an easy way to start the conversation, and the community can take it from there.”

This year, one of the Keeping History Above Water conferences will be streamed virtually and for free from Trinidad and Tobago so that anyone interested in the increasing and varied risks posed by sea level rise to historic coastal communities can learn more. Visit historyabovewater.org for more.